Scope

User privacy on the Web is a multifaceted topic which defies easy answers often causes great disagreement

and debate. This document does not seek to analyse all facets of Web privacy. However, it does recognise

the fact that awareness of Web privacy issues is on the rise, both on the part of Web users and Web developers.

Over the past three years, the W3C has run several workshops and launched two new groups on topics related to

user privacy. The IETF has also strongly expanded its activities in the privacy space. Strong privacy laws

are in force in many parts of the world and being discussed in others.

Privacy on the Web is a topic that overlaps technical, social, regulatory and emotional barriers and is

therefore difficult to pin down when creating a technical specification. This paper therefore chooses to

focus on a deliberately limited subset of the problem space.

In this document we consider only those aspects of privacy and APIs that can be mitigated by API designers,

such as providing more information than is necessary for a given operation, not making it possible for the

user to control what information is being shared, and device fingerprinting. Conversely we do not cover other

privacy attacks such as tricking the user into providing information or maliciously using collected information

in ways that were not agreed to by the user. We have chosen this focus because well-designed APIs from the

privacy standpoint should provide a solid foundation for better user privacy in general, because they can help

address the problem at the root, and because we feel that they form a coherent whole.

It is important in reading this document that its ambition is simply to capture known best current practices

in API design in order to help spread them amongst groups, and so as to provide a common starting point on top

of which further privacy-enhancing API design patterns can be built. Its content is therefore not expected to

remain static for all of eternity, but rather to evolve so as to capture the community's knowledge

of this domain.

Privacy is a very broad topic that covers most parts of the technological stack as well as its relationship

to society. Rather than attempt to “boil the privacy ocean” and address the entirety of the issue at once,

it is the firm opinion of this document's authors that the users' privacy will be best served by addressing

the problem separately at each layer that it touches so as to avoid the architectural infelicities involved

in crossing layer boundaries with a single solution. Such well-scoped changes can furthermore be deployed

quickly and provide the greater leverage of being accepted in their respective communities. There are

therefore many privacy issues that this document does not address; we can only encourage others

to attempt similar exercises across the board. Note that while the TAG's remit reaches well beyond API

design and thus leaves the door open for further TAG work on privacy, this specific domain was selected

as an area of high priority due to the great number of APIs being designed concurrently at this time.

Background

This section introduces some of the background thinking and history behind the development of this

document.

Data Minimisation

In their 1975 paper The Protection of Information

in Computer Systems, computer scientists Jerome Saltzer and Michael Schroeder articulated a principle of

“least privilege:”

Every program and every user of the system should operate using the least set of privileges

necessary to complete the job. Primarily, this principle limits the damage that can result

from an accident or error. It also reduces the number of potential interactions among privileged

programs to the minimum for correct operation, so that unintentional, unwanted, or improper uses

of privilege are less likely to occur.

Although written long before the Web came into use and firmly form a security standpoint, Saltzer

and Schroeder's definition could apply as easily to the distributed world of Web applications as

they did to time-sharing mainframe programming of the 1970s.

Today, client-side Web applications are increasingly playing a role as intermediates for our personal,

privileged information between the devices we carry and applications residing somewhere on the Internet.

In the “Terminology for

Talking about Privacy by Data Minimization: Anonymity, Unlinkability, Undetectability, Unobservability,

Pseudonymity, and Identity Management”, Andreas Pfitzmann, Marit Hansen, and Hannes Tschofenig

succinctly define minimisation as a strategy towards implementing enhanced privacy in (personal) data

collection and usage:

Data minimization means that first of all, the possibility to collect personal data about others

should be minimized. Next within the remaining possibilities, collecting personal data should be

minimized. Finally, the time how long collected personal data is stored should be minimized.

Data minimization is the only generic strategy to enable anonymity, since all correct personal data

help to identify if we exclude providing misinformation (inaccurate or erroneous information, provided

usually without conscious effort at misleading, deceiving, or persuading one way or another)

or disinformation (deliberately false or distorted information given out in order to mislead or deceive).

Furthermore, data minimization is the only generic strategy to enable unlinkability, since all correct

personal data provides some linkability if we exclude providing misinformation or disinformation.

In attempting to apply these principles to the area of client-side Web APIs, the W3C Device APIs Working

Group has refined this definition within their Device

API Privacy Requirements.

-

APIs MUST make it easy to request as little information as required for the intended usage. For

instance, an API call should require specific parameters to be set to obtain more information,

and should default to little or no information.

-

APIs SHOULD make it possible for user agents to convey the breadth of information that the requester

is asking for. For instance, if a developer only needs to access a specific field of a user address

book, it should be possible to explicitly mark that field in the API call so that the user agent can

inform the user that this single field of data will be shared.

-

APIs SHOULD make it possible for user agents to let the user select, filter, and transform information

before it is shared with the requester. The user agent can then act as a broker for trusted data, and will

only transmit data to the requester that the user has explicitly allowed.

Privacy by Design

“Privacy by design” is a relatively loaded term which has taken on multiple different definitions depending

on context. However, since it is the term of trade that has been in use in groups tasked with defining

Javascript APIs over the past few years, we have chosen to keep it, while ensuring that a specific definition

is provided here.

Within the scope of this document, privacy by design is a design approach that takes malicious

practices for granted and endeavours to prevent and mitigate them from the ground up by applying specific

patterns to the creation of Javascript APIs.

It is particularly important in privacy by design that users be exposed to as few direct privacy decisions as

possible. Notably, it should never be assumed that users can be “educated” into making correct privacy decisions.

The reason for this is that user typically interact with their user agent in order to accomplish a specific task.

Anything that interrupts the flow of that task's realisation is likely to only be given as cursory a thought

as possible. Therefore, requiring users to make privacy decisions whilst in the middle of accomplishing a task

is a recipe for poor decisions.

There are two primary issues that privacy by design seeks to address within the scope of Javascript APIs.

Poor Information Scoping

In order to accomplish a given operation, a Web application may legitimately require access to some of

the user's private information. The issue here is that in providing access to the required information

can sometimes entail exposing a lot more information. For instance, when the user wishes to share one

event in their calendar, the entire calendar becomes available; or where the user needs to share the

name and email addresses of some of their contacts, the phone numbers, pictures, home addresses, etc.

of these contacts are also returned.

Device Fingerprinting

Users are routinely tracked across the Web through the use of cookies and other such identification

mechanisms. In many cases, these tracking methods can be successfully mitigated by the user agent, for instance

by only returning cookies for the top level window in the browsing context (as opposed to providing them

for iframes for instance).

Fingerprinting circumvents this by looking at as many of the unique features of a user agent in order to

ascertain its uniqueness. For instance, it may look at screen resolution, the availability of specific

plugins, at the list of fonts that are installed on the system, the user agent string, the timezone, and

a wealth of information that user agents tend to provide by default. Taken one by one, none of these

data are sufficient to identify a single user, but put together they collect enough bits to narrow

the identification down to just the one person — especially if you take into account the population

that visits a given site or set of sites.

A very good demonstration of fingerprinting, alongside with a paper detailing the approach, are

available from Panopticlick — How Unique and Traceable is Your Browser?

Privacy-Enhancing API Patterns

The Web application platform requires the availability of a vast array of functionality that can greatly

vary in nature. As a result, not all APIs can look the same, and no single approach can be applied automatically

across the board in order to take privacy into account during API design. This section therefore lists

patterns that API designers are expected to adapt to the specific requirements of their work.

Action-Based Availability

We seldom pause to think about it, but the manner in which mouse events are provided to Web applications

is a good example of privacy by design. When a page is loaded, the application has no way of knowing

whether a mouse is attached, what type of mouse it is (let alone which make and model), what kind of

capabilities it exposes, how many are attached, and so on. Only when the user decides to use the

mouse — presumably because it is required for interaction — does some of this information become

available. And even then, only the strict minimal is exposed: you could not know whether it is a

trackpad for instance, and the fact that it may have a right button is only exposed if it is used.

This is an efficient way to prevent fingerprinting: only the minimal amount of information is provided, and

even that only when it is required. Contrast it with a design approach that is more typical of the first

proposals one sees to expose new interaction modalities:

var mice = navigator.getAllMice();

for (var i = 0, n = mice.length; i < n; i++) {

var mouse = mice[i];

// discover all sorts of unnecessary information about each mouse

// presumably do something to register event handlers on them

}

The “Action-Based Availability” design pattern is applicable beyond mouse events. For instance,

the Gamepad API makes

use of it. It is impossible for a Web game to know if the user

agent has access to gamepads, how many there are, what their capabilities are, etc. It is simply

assumed that if the user wishes to interact with the game through the gamepad then she will know

when to action it — and actioning it will provide the application with all the information that

it needs to operate (but no more than that).

The way in which this pattern is supported for the mouse is simply by only providing information

on the mouse's behaviour when certain events take place. The approach is therefore to expose

event handling (e.g. triggering on click, move, button press) as the sole interface to the device.

The Gamepad API supports this in a different, but equally good, fashion. The navigator.gamepads

array is initially empty, and only becomes populated when a gamepad has been interacted with (and then,

only with those of the connected gamepads that have been manipulated). Once they have been interacted with,

for the lifetime of the document these gamepads become available in the array and can be queried for a limited

(but essential) set of information.

Graceful Degradation

Graceful degradation is the principle according to which a system will continue to operate at the

best of its capabilities despite the fact that a given piece of functionality may be missing.

While commonly relied upon in Web technology, notably for document styling, it also has value

as a tool that can minimise device fingerprinting.

A good example of this pattern in action is the Vibration API.

Traditional APIs for vibration would make it possible for the developer to detect whether the device

on which her application is being run features a vibrator. Additionally, attempting to trigger

vibration would likely cause an exception or other such code-detectable failure. This would produce

at least one bit of additional fingerprinting information, possibly more if the device's vibrators could be

further investigated.

The Vibration API approaches this problem differently: when a device does not support actual vibration,

it does not surface this information. Calling navigator.vibrate(1000) will work just as

well as if a vibrator had been present, and indistinguishably from that set up. In addition to making

the code more robust, this approach therefore also contributes to fingerprinting reduction.

User Mediation

By default, the user agent should provide Web applications with an environment that is privacy-safe

for the user in that it does not expose any of the user's information without her consent. But in

order to be most useful, and properly constitute a user agent, it should be allowed to

occasionally punch limited holes through this protection and access relevant data. This should

never happen without the user's express consent and such access therefore needs to be mediated

by the user.

At first sight this appears to conflict with the requirement that users be asked to make direct privacy

decisions as little as possible, but there is a subtle distinction at play. Direct privacy decisions

will prompt the user to provide access to information at the application's behest, usually through

some form of permissions dialog. User-mediated access will afford a control for the user to provide

the requisite information, and do so in a manner that contextualises the request and places it in

the flow of the user's intended action.

A good and well-established example of user-mediated access to private data is the file upload form control.

If we imagine a Web application that wishes to obtain a picture of the user to use on her profile,

the direct privacy decision approach would, as soon as the page is loaded, prompt the user with a

permissions dialog asking if the user wishes to share her picture, without any context as to why

or for what purpose. Conversely, using a file upload form control the user will naturally go through

the form, reach the picture field, activate the file picker dialog, and offer a picture of her choosing.

The operative difference is that in the latter case the user need not specifically think about whether

providing this picture is a good idea or not. All the context in which the picture is asked for is

clearly available, and the decision to share is an inherent part of the action of sharing it. Naturally, the

application could still be malicious but at least the user is in the driving seat and in a far better position

to make the right call.

A counter-example to this pattern can be seen at work in the Geolocation API [[GEOLOCATION-API]]. If a

user visits a mapping application in order to obtain the route between two addresses that she enters, she

should not be prompted to provide her location since it is useless to the operation at hand. Nevertheless,

with the Geolocation API as currently designed she will typically be asked right at load to provide it.

A better design would be to require a user-mediated action to expose the user's location.

This approach is applicable well beyond file access and geolocation.

Web Intents are

currently being designed as a generic mechanism for user-mediated access to user-specific data and

services and they are expected to apply to a broad range of features such as address book, calendar,

messaging, sensors, and more.

Minimisation

Minimisation is a strategy that involves exposing as little information as is required for a given

operation to complete. More specifically, it requires not providing access to more information than

was apparent in the user-mediated access or allowing the user some control over which information

exactly is provided.

For instance, if the user has provided access to a given file, the object representing that should not

make it possible to obtain information about that file's parent directory and its contents as that is

clearly not what is expected.

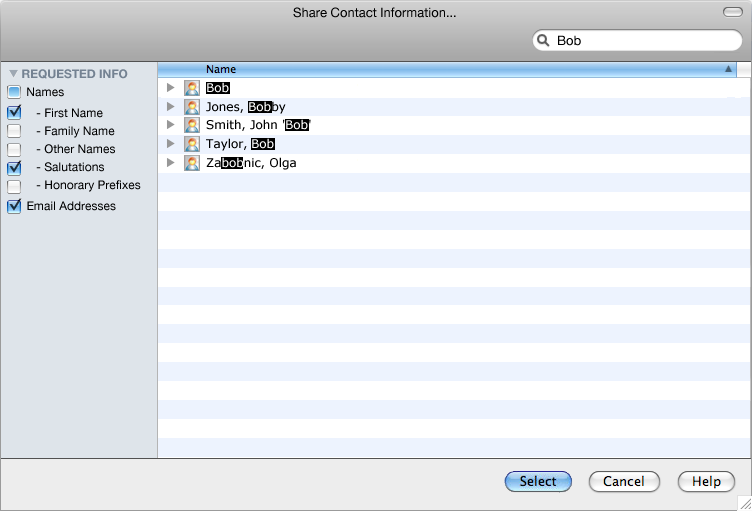

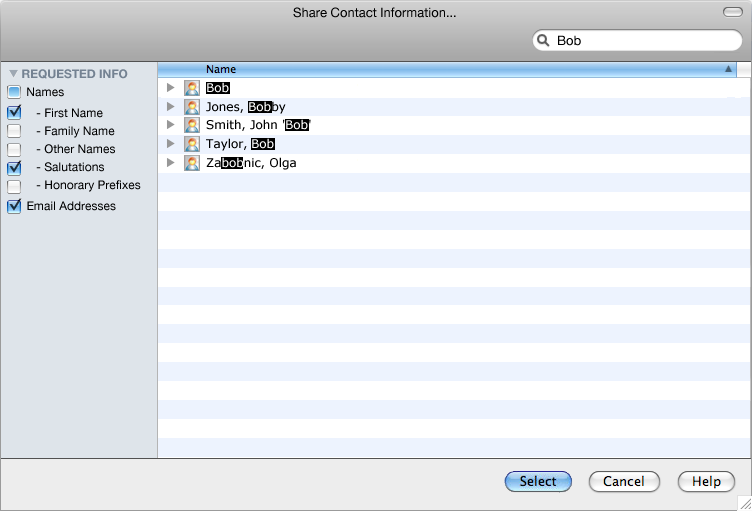

During user-mediated access, the user should also be in control of what is shared. For example, if the

user is sharing a list of contacts from her address book it should be clear which fields of these

contacts are being requested (e.g. name and email), and she should be able to choose whether those

fields are actually going to be returned or not. An example dialog for this may look as follows:

In this case the application has clearly requested that the First Name, Salutations, and Email Addresses

fields be returned. If it seems unnecessary to the user, she could unselect for instance First Name before

providing the list of selected contacts and the application would not be made aware of this choice. Such

a decision is made in the flow of user action.

The above requires the API to be designed not only in such a manner that the user can initiate the mediation

process of access to her data, but also so that it can specify which fields it claims to need.